How a bell works...

A detailed look at how we ring, how a bell works and what all the parts of a bell are called. It also looks at why we need to be so careful about how we work in a belfry or ringing chamber.

Raising a Bell

Background

Bells are kept in the ‘down’ position when not in use. They hang with mouths pointing downwards, where they can safely be worked on and will not pose a risk to anyone who ventures into the belfry.

Before they can be rung for changes, we ring the bell to the ‘up’ position. This is done by swinging the bell to and fro, until it reaches a point where it passes over the highest point.

The Raise

During the process, you will see the bell start by swinging and chiming on one side of the bell. The bell gradually swings more and more as the ringer pulls at just the right time. The process is just like pushing a child on a swing; careful pushing building up momentum. Once the bell is swinging 45° each way, the clapper will start striking the near as well as the far side of the bell.

As it swings higher, the bell will go slower and slower. It also gets to the balance point when it is completely upside down with pointing mouth upwards.

At this point you will see the bell’s wooden stay, gently pushing the slider mechanism backwards and forwards below the bell. Finally, the ringer will set the bell in the ‘up’ position. The bell is gently allowed to cross the balance point and push the slider up against its’ end stop.

The bell is now ready for change ringing.

Safety

In the ‘Up’ position, the bell could be very dangerous to anyone who pulled the rope not realising it was up or who did not know what they were doing. If left like this, a sign will be posted warning ringers to be careful and non-ringers not to touch or enter the area.

Ringing a Bell

The bells are all finely balanced ready for ringing in the up position. It only takes a relatively small effort to pull them over the balance and swing them through a full circle. Once over the balance the bell falls naturally and is therefore very dangerous if you do not know what you are doing. Bells weigh anything from 150Kg to 2000Kg and therefore have a lot of stored up energy; so care needs to be taken with bells that are ‘up’!

Bells are docile and easily controlled in the hands of a trained ringer. The aim is to get the bell close to its balance point after every pull. This way the bells speed can be controlled and the bell set back to the balance at any time.

Hand Stroke and Back Stroke

The video shows the bell ring alternately at hand and back stroke. Hand stroke is when the ringer pulls a striped wooly grip called a Sally. At back stroke, the rope will go up above the ringers head and it is the tail-end which is pulled back down.

The slider mechanism works at both strokes and it is quite possible to ‘set’ the bell at back as well as hand stroke.

The skill of ringing…

Bell handling is about getting the pull just right and the bell to the balance point every time. Ideally, the slider will be gently moved to and fro, but never hit. It should only reach the end stops when the bells is being set. It is quite possible to hit the slider with the stay if the ringer over pulls the bell too much. This might crack, or even snap the stay… With no stay, the bell will not stop. It turns right over and the rope disappears through the ceiling as it wraps around the wheel! If a stay fails, letting go is essential or the ringer will end up with bad rope burns or much worse! This is a fairly rare occurrence and generally only happens to learners who are not being supervised well enough.

Lowering a Bell

The bells will be lowered to the ‘down’ position at the end of ringing. This means they are once more hanging free and relatively safe.

The exception to this is when there is another ringing session in the near future… perhaps later in the day, or the next day. In this situation, warning signs will be hung on the ropes in the ringing room. The belfry will also be securely locked to make sure no one can touch.

The process of lowering is far less energetic than raising because the bell will naturally want to loose its momentum. The job of the ringer is to keep the rope taught and make sure any slack is coiled up. The bell will gradually speed up as the swing reduces until it gets to below 45°. At this point it stops striking on both sides of the bell and the strike rate will halve.

Chiming

The bell will be chimed at the very end of the lower. Chiming is when the bell is swung just enough to keep the clapper tapping against the bell. This is much like bouncing a ball on a racket; if you get the ball in the right spot, it can be bounced with almost no effort or movement. Even a very large bell can be chimed with minimal effort, once the clapper is swinging.

Raising in Slow Motion...

This is the same raising video, but running 8x slower! (Apologies for the flicker… this an interference pattern caused by fluorescent lights in the belfry… We will re-shoot without the house lights in due course!)

- You can clearly see how the clapper moves and when it strikes the bell… The single and then double striking and how it moves with relation to the bell.

- You can also watch the rope and pulley block below the bell… The wheel pulls the rope towards the camera at hand stroke and up the far side of the wheel at back stroke.

- Finally, take time to look at the interaction of stay and slider as the bell reaches the balanced ‘up’ position. See how gently the stay pushes the slider back against the end stop.

Bells can be very dangerous...

Most towers will have signs warning of danger. These are on the wall or hung on the bell ropes when the bells are in the up position.

Experienced ringers know to be cautious and always check all the bells are down when they enter a tower. Very cautiously trying to swing the bell is the test, but it requires experience and care! This is particularly important if the tower has no regular team in charge to supervise a visit.

Even large bells will swing a tiny amount when gently pulled… however, a bell that is up, will bounce against its stay and feel completely different.

A snapped rope...

In this clip, the rope of a large bell, snaps below the sally. The short rope goes too high to keep hold of and flails around.

Everyone sets their bell then stands well back. Luckily, there is nothing close for the flailing rope to catch hold of, so the whole business is well managed… But the sheer violence in the loose rope is very clear. Most ringers will experience an incident like this at some point in their ringing career. It is something they will always remember and be keen not to repeat!

It makes a very strong case for good maintenance plans, particularly the ropes!

A dangerous incident...

This clip shows a ringing room which doubles as a store room. This is not uncommon in small churches.

The ringers make the dangerous error of not clearing the room before attempting to ring… The resulting consequences are frightening and make it obvious why a cluttered ringing room is a very bad idea and loose ropes are extremely dangerous. Luckily, the bell is small, comes down quickly and no one was badly hurt.

Experienced ringers will always make sure those not ringing keep their feet flat on the floor and no one leaves anything lying around. Ropes will catch around anything loose!

Parts of a bell..

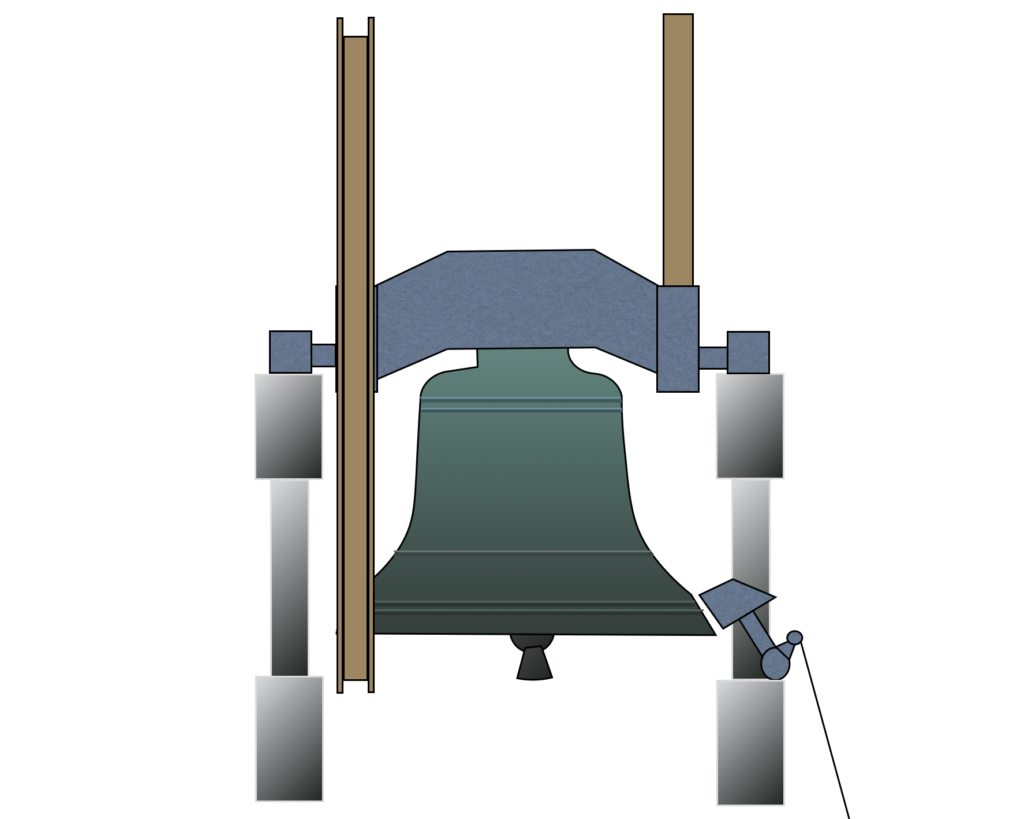

The Frame

Modern frames are made from steel and use triangular ‘A’ or square ‘H’ sections to create a strong, rigid structure. Older frames can be made of wood and will need lots of care to keep everything tight and rigid. The aim of the frame is to pass all the forces the bells create into the main structure of the tower. This why you will be able to feel taller towers swaying when the bells are ringing.

Headstock

The headstock is a large piece of metal which forms the axel about which the bell turns. On old installations, it might be wood. The bell is bolted to the headstock. It needs to be very strong as it takes all the forces the fast moving bell creates. The bell will be fastened by four large bolts which will take all the strain.

Older bells like the Pebworth tenor… have canons at the top of the bell. These are decorative loops of bronze; all part of the original casting and were originally used to strap the bell to a wooden headstock. They are not used with modern steel headstocks.

Many bells had their canons sawn off when rehung. Our older bells still have their cannons and even our modern bells have them (but not as decorative!). This makes sure all the bells show similar characteristics when ringing. Special U shaped headstocks are used with canons along with very long bolts to secure the bell.

Wheel

The Wheel will be between 1.2m and 2m in diameter and is attached to the headstock. It is the means by which the rope is able to move the bell. The rope is attached at the top of the wheel with plenty of spare wound around the centre. This allows for shrinkage in wet weather and stretch when it is dry. As a result, a good steeple keeper will adjust the lengths of the ropes on a regular basis.

Often ropes will be compound in design… Terelyne synthetic rope is used at the top as it is far less susceptible to damp and weather rot. Traditional hemp rope is used for the lower portions where it is likely to be handled as terylene is not kind to ringers hands.

A good set of ropes need regular checking for wear, but should last many years. They are particularly prone to wear around the garter hole, where they are constantly being flexed through 180°.

The garter hole is leather lined and where the rope passes into the centre of the wheel for tying off. The rope then passes around the wheel and down to the pulley box.

The pulley box makes sure the rope stays aligned with the wheel as it rotates. It then guides the rope past the frame and through the floor into the ringing chamber below.

Stay

A Stay will be attached to the headstock opposite the wheel. It is a long straight piece of wood and generally made of Ash. It is designed to stop the bell going beyond the balance point and tipping right over. If the rope is over pulled or not caught, the stay may get damaged or even broken. If the stay breaks you need to let go of the rope… The bell will continue turning and the rope will disappear through the ceiling at great speed!

Stays should last for a very long time if treated with care. However, they are expendable items and bells used by learners are prone to getting the odd bashing.

Stays are checked by the steeple keeper on a regular basis to look for evidence of cracks or other damage. It is particularly important around the bolts attaching it to the headstock. This it the weakest point and also where leverage is at its highest.

Slider

The slider is a hinged and curved piece of wood that sits below the bell. It can move about 2 feet between wedge shaped stops, allowing the stay and bell to pass the balance point. Generally, it will be the stay which breaks when hit and not the slider. Adjustment of the slider is critical to make sure the loads on the stay are correct and the bell is not too far over the balance when set.

If the stops are too far apart, the ringers may not be able to pull the bell over the balance and the stresses on the stay may cause premature failure… too close and the bell will not set.

Clapper

The flight is at the bottom of the clapper. It is a conical shaped piece of metal which helps the clapper swing and strike correctly.

The ball is above the flight, and it makes contact with the bell. We have fitted pieces of old motorcycle tyre around the ball to provide muffling of the bell. By simply rotating the tyre, the bell can effectively be silenced for 1:1 training activities… This seems like a minimal kindness to our neighbours!

When we half muffle the bells for remembrance day, we strap a leather pad around one side of the ball. The bell then strikes loudly at hand stroke, but much more quietly at back stroke… It is important to make sure you do all the bells on the same (back stroke) side!

The shaft is above the ball and beyond that is a simple hinge type bearing. This allows the clapper to move in the same direction as the bell. The bearing needs to be greased regularly and may need to be re-bushed if it becomes too worn. A worn bearing would allow lateral movement of the clapper, which may in turn damage the bell.

In the picture, you can clearly see the four bolts which secure bell to the headstock. You can also see where the bell was tuned on a lathe. It is machined at specific places on the bow and inner waist. This tunes not just the pitch we perceive, but also the tonal quality of the bell.

Crown Staple

The clapper is attached to the headstock by the hinged bearing at the top of the flight. The staple is part of this bearing assembly. It is a long bolt which passes through the bell and headstock and is fastened with a large nut.

Because this is a point where lots of forces combine and regular shock waves are transmitted from ball through shaft, it is normal for these nuts to have a split pin. This stops the staple working loose or the shaft and bearing rotating. A clapper falling out of a bell is not only frightening to hear, it could also do a lot o damage!

Bearings

Modern bells have sealed self aligning roller bearings mounted on the frame. These are mated to the gudgeons… large axel like protrusions from the headstock. Older bells may still have ‘plain bearings’ where there are no real moving parts. Plain bearings will need regular greasing and maintenance and can be problematic. They were phased out about 120 years ago… but there are still plenty of them in service!

Clock Hammers

Clock hammers and chiming apparatus can often be attached to the frame. They generally strike the outer surface of the bell and can be mechanical or electro-mechanical. It is essential, that hammers are disabled before ringing full circle, or they can activate and drop into the path of the fast moving bell…. damaging or possibly destroying both.

Although we have a clock at Pebworth, it does not strike, so this is not an issue. However, we are always very cautious about looking for bypass mechanisms when visiting other towers!

If you want to know more, then the links below might prove useful.

The CCCBR have a very good belfry maintenance section and Taylors of Loughborough are the one remaining foundry in the UK… having been in business for nearly 200 years. Also, there is a very good description of metal casting from Kylar Mack’s Blog with lots of interesting links, including to the National Bell Festival site… which is an US site dedicated to bells and bell ringing of all types.