Introduction

Ringing with others as part of a team is all about striking…. Striking your bell at exactly the same speed as the other bells and spacing all the bells evenly. It is all about the sound of the bells…

To get good striking, we need to have excellent bell control, so the bell does what we want… But we are also visual creatures and use the cues the moving ropes provide to help us place our bell. However, this can be deceiving, as the relationship between what we see and the sounds we produce is variable… and therein lies a problem!

Ringing rounds is relatively easy as everything stays constant and the adjacent bells are of a similar size. However, as you get involved with ringing changes, it gets harder. The more bells there are, the more they get mixed up and the more there is to listen to and sort out. And the size of the bell you follow will also make a difference.

Good striking is about listening and learning to make adjustment to any visual cues we use. It takes practice and experience, but understanding the issues will also help a great deal.

When you have read about the issues, the next stage is to improve your listening skills, so you might like to start training your ear with our listening games…

Open or Closed

When we ring, we generally aim to space all the bells as evenly as possible, but with one notable exception: Hand stroke Lead! At hand stroke, the person leading is expected to leave a gap, just large enough to fit one extra bell in. It’s a punctuation mark to set the pace and create a reference point for listening; helping with working out our position in a change. Without a gap, it would be very difficult to know whether you are in 2nd or 7th place. And if you ring even bell methods and all the bells are moving, the tenor might be anywhere! Leaving a gap at handstroke is generally referred to as Open Hand Strokes.

If you ring with open hand strokes, the changes will come in pairs; one hand and one back stroke.

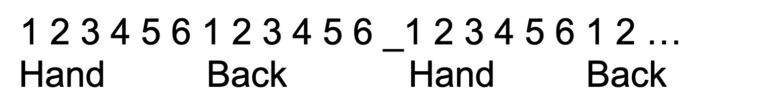

A visual representation might look like this:

Rounds on 6

With 6 bells, there should be 13 spaces or beats in which to place the bells… the last being the gap!

Click the icon below to listen to ringing with open hand strokes…

Rounds on 8

For 8 bells, there will be 17 spaces. 8 at hand and 8 at back, with the last being empty.

If we extend the idea… for 10 bells, there will be 21 beats and for 12 bells, 25 beats. It is 2 x the number of bells + 1 for the gap.

Musically, this will seems strange, because the changes break up into measures (bars) of 13, 17, 21 or 25 beats. This is not something we normally expect… Music normally divides into bars of 2, 3 or 4 beats, like a march or waltz… but for ringing it is what we do!

Devon Call Changes

Method ringers have traditionally used open hand strokes and that is the norm for most ringing. However, if you visit the world of the expert call change ringers in the West Country, you will hear a different style of ringing. Unlike method ringers, the call change specialists ring well below the balance point of the bell. Once they start ringing, they will partially lower the bell so it rings much faster. Because of this, the clapper provides far less damping and the hum of the bells build into a much thicker, more resonant texture… It is very much like the great ‘hum’ you hear when lowering in peal. Only at the end of the call changes, will the order be given to slow down and raise the bells back to the balance, ready to stand.

Because the bells are well below the balance, open hand strokes become quite problematic, so the gap is removed. We call this closed hand strokes or cart-wheeling. When ringing call changes, the slower nature of the changes and instructions, means that the missing punctuation marks are less significant. Call change ringing with closed hand strokes is far from easy, but when done well, creates the most remarkable sound!

Above is a link to an excellent example of Devon style call changes… rung at the 7cwt, 6 at Meavey, Dartmoor. The sound is quite entrancing and so very rich… Note that most of the ringers have a coil during the ringing… something which would definitely be frowned upon by most method ringing bands.

Below are some links to other sites with more information about call changes and the way bells are rung in the south-west.

Hand, Ear and Eye Co-ordination

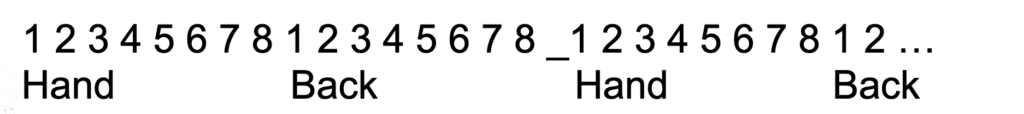

The first big problem any new ringer needs to appreciate is that a bell does not ring immediately after you pull the rope. In reality, you pull, the bell falls, and only about a second after that does the bell actually strike. If you are ringing the treble this will probably be quite obvious (…look to …trebles going …she’s gone… …dong!). But for bells in the middle or back part of the order, it is perhaps less so.

The importance of this is simple…. It means that when you watch and follow another bell, there will also be a delay between:

- what you see…

- your actions that place your bell accurately…

- and hearing the results as your own bell strikes in the sequence…

In summary..

Because of the delay between what we see/do and what we hear, linking the two can be tricky.

As visual creatures, we will naturally assume our eye is correct, even when it is not.

We need to learn to listen and relate that back to what we saw and did, seconds before!

Size Matters...

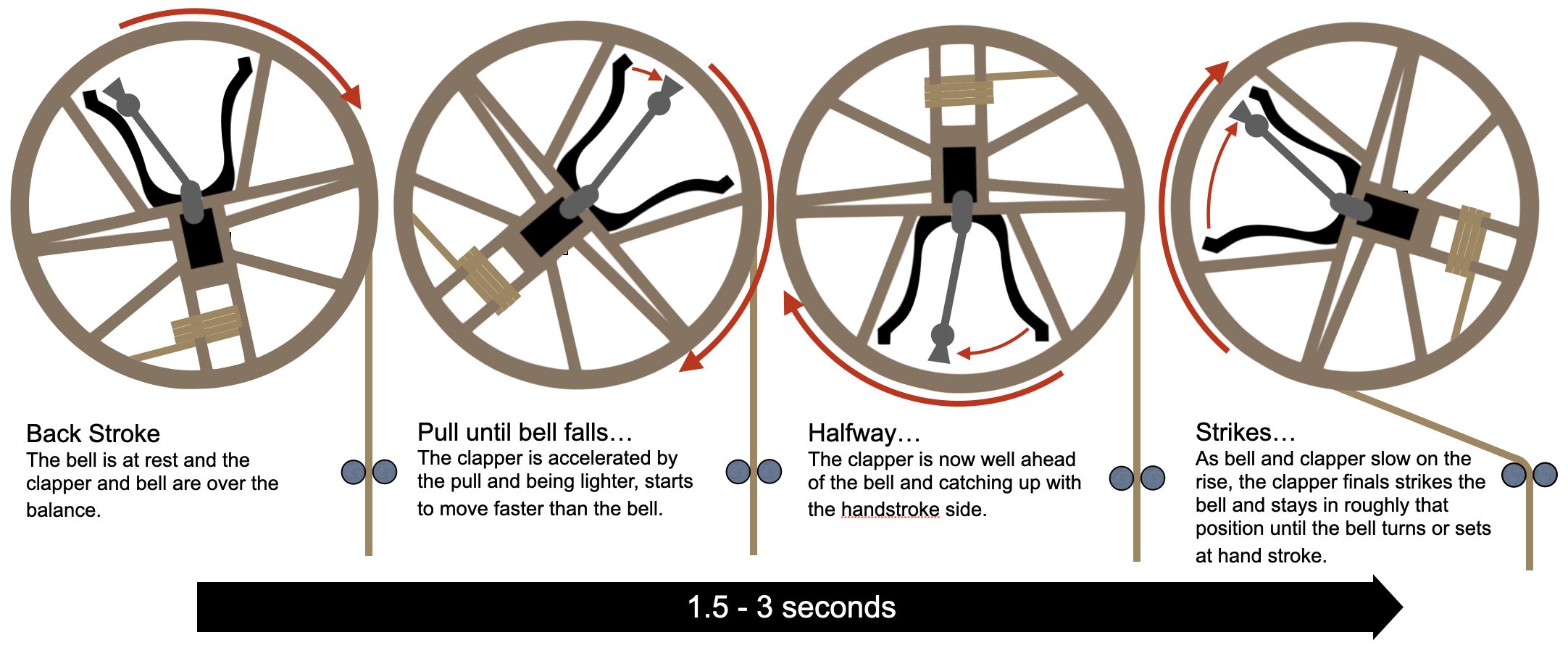

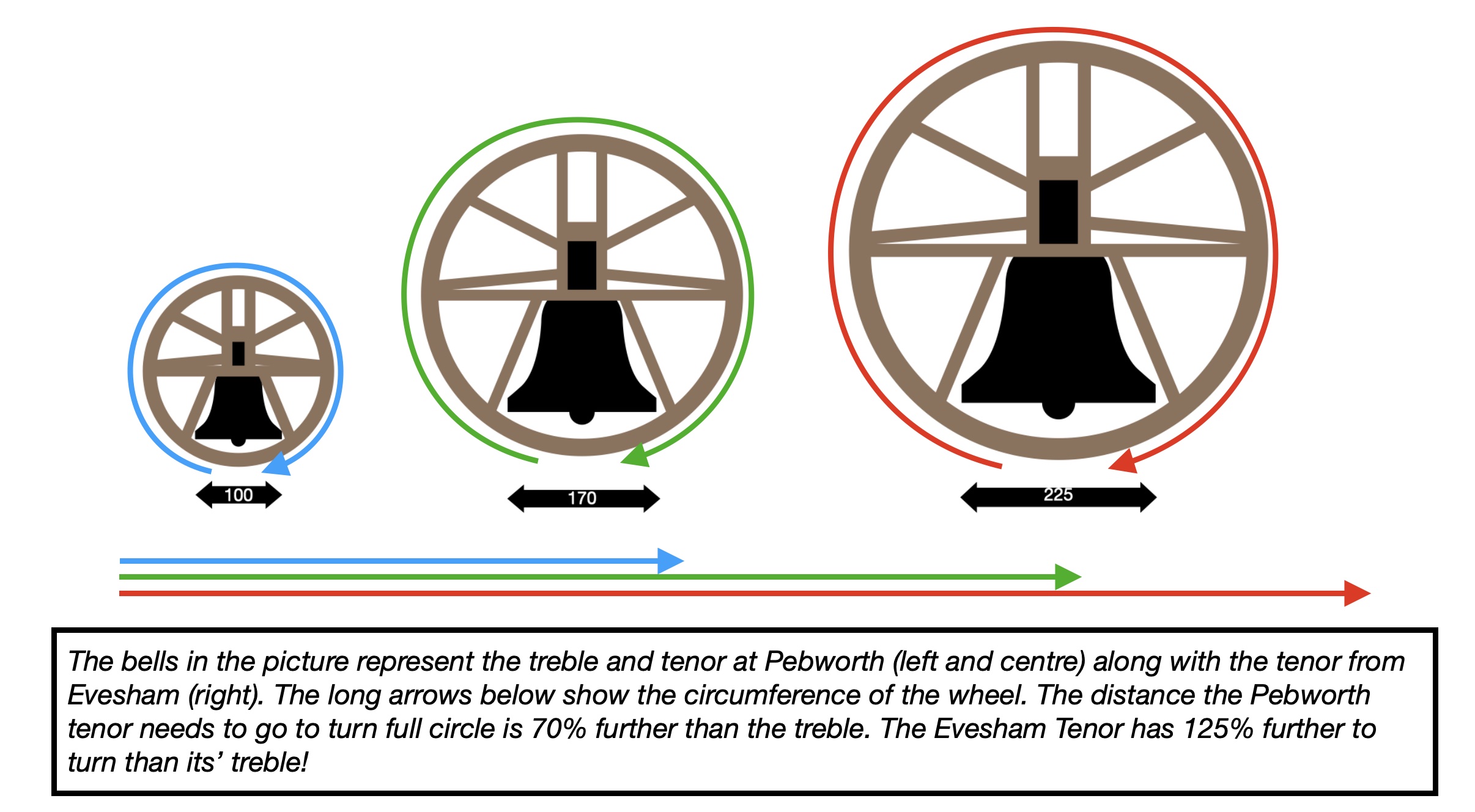

The delay in striking is caused by the speed at which a bell turns… and that will also be dependent on its size. The bigger the bell, the further it has to go and the longer it takes to turn. A light ring will seem to go much faster than a heavy ring. This in itself is not surprising; all large things appear to move more slowly. This is due to the rules of momentum and the larger amounts of energy required to make things happen – but it is mostly an illusion created by proportions and everything being much larger and therefore further apart.

As we add more bells to the circle, this problem takes on a new facet. The more bells you have, the wider the range of weights and speeds. So a 10 or 12 bell tower will have both heavy and light bells… often with very big differentials. As an example, the difference between the turning time of the smallest and largest bells at Pebworth is nearly 70% longer because the tenor is 3x the mass and has a much larger swing circumference. At Evesham, this increases to more than double because the tenor is 8x heavier than the treble!

The implications for striking are enormous… The bigger weight differential, the more allowances need to be made.

So the little bells will have to ring much wider over the bigger bells than they do over each other… The bigger bells will ring much closer to the little bells than they do with their largest neighbours.

This phenomenon applies in all towers, however with a moderate sized ring of 6, the effect is less marked than with a heavy 12…

If you visit a heavy ring with higher numbers or bells, the little bells will need to leave more than double the gap when following the biggest bells. For the biggest bells, the opposite is true. When following the smallest, visually, they appear to be ringing at the same time or even slightly before them – because of the longer turning period! It will sound lovely, but can make rope sight something of a nightmare!

In summary…

Visually, bigger bells ring closer to smaller bells…

…and visually, smaller bells give bigger bells extra space.

The bigger the size differential… the bigger the visual issue.

In reality, no one is ringing closer to anyone else… it is just an optical illusion!

It is all about making it sound right!

Odd Struck Bells

Odd-struckness is a way of describing a bell which does not strike in the same predictable way as the other bells in a tower. In reality, every bell will be unique and have its own foibles… however, some may have more significant differences. These will be characterised as ‘odd-struck’!

This is another purely visual problem… It is about hand/eye co-ordination and it may need to be different for different bells, irrespective of weight. It is very likely that a blind ringer would be far less aware of this concept. They would strike their bell purely by hand/ear coordination.

The concept of odd-struckness can be difficult to comprehend. Bells are as complex as the people who ring them and there can be a variety of reasons why a bell might be noticeably odd-struck.

Odd-struckness can affect hand stroke, backstroke or both…. It could be that the clapper is stiff and it will strike later than expected. It could be a slight offset in the centring of the bell on the headstock, and the bell will strike later/earlier at one stroke than the other. If the profile (shape) of an ancient bell is slightly different, this may also cause odd-struckness!

Odd-struckness is a problem for the entire team...

For example:

the person ringing a significantly odd-struck bell, may need to ring closer than normal at hand and/or backstroke when compared to the other bells – This is because their bell strikes slightly later on the turning circle than the others. It will make the visual pattern of the moving ropes look slightly uneven.

The rest of the team will need to do the opposite and provide more space at hand and/or backstroke when following the odd-struck bell… But only that bell!

Of course, in reality odd-struckness can be late or early.

When there are two or more very odd-struck bells, it gets even more complex, with different gaps required for each bell… Coupled with weight differentials between the biggest and smallest bells; every stroke, for every bell may be visually different!

The Rhythm Method...

Listen not Watch…

If you ring by rhythm, then striking gets much easier. The more you listen, the less you will rely on sight… and sight is actually the biggest problem with striking, because as we have discovered, there is a variable offset between what you appear to be doing visually and the sound the bells produce.

Every Illusion is Unique…

In practice, every bell is unique and there may be differences between hand and backstroke, but these differences are fixed because they relate to that bell, irrespective of who you are following…. so once you have got a measure of the speed you need to ring at and how the bell strikes, the rhythm remains consistent. If another bell is odd-struck, you might appear to be ringing closer at one or other stroke, but in reality you are not, and aurally, you will not really be aware of any issue… provided it too is being correctly placed and you are not watching it for your cue!

Developing your ear, so you can hear your bell striking and create a consistent rhythm to your ringing, is an excellent way to solve the problem.

Listening takes effort…

In reality, this is much harder than it sounds….especially once you start ringing methods! We are visual creatures and sight is our primary sense. Even the best ringers will use sight to work out what is going on, so we all need to learn to trust our ear and only use our eyes for crude approximation and checking orders. Of course, good striking also relies on the whole team being able to do the same, which will become increasingly difficult to do with an inexperienced band.