Intervals

Learn how we measure and describe the musical gap between two bells.

If you have not yet read our article about the Sound of Bells, you might find it helpful to do so before reading this page. It covers the basic theory of sound and music and provides underpinning knowledge which will be useful when thinking about the specifics of musical intervals.

What are Intervals?

The term Interval is used by musicians to describe the gap between two different notes. It is a measure of how many semi-tones separate them. With twelve possible notes in an octave (including the sharps and flats), there are also 12 possible intervals between the first and last. Many occur multiple times as you go from any one note to every other… which of course, is exactly what change ringing is all about!

With 8 bells, even though we are only using 8 notes, we will still use all 12 intervals as we work through the musical permutations we call changes, so understanding more about them is useful knowledge and helps explain why some permutations are less desirable than others.

Categories

Just like keys, intervals use the terms major and minor, along the terms perfect, augmented and diminished. Generally, the major intervals will be the brightest sounding ones and the minor ones will be less so. Perfect intervals are the ones that are most plain because they are the closest related to each other. An augmented/diminished interval is one which is much less frequently used and covers anything which major, minor and perfect intervals cannot.

Relative and Perfect Pitch

For most of us (99.9%), when we hear two notes, we can tell the difference between them. This is called ‘relative pitch’ and it allows us to judge how much higher or lower one pitch is compared to the other. Using this skill, we can make sure our voice is at the same pitch as others when singing in unison. Just like any skill, it takes effort and practice, but most can learn it to some degree… Many will develop this without any help at all. With practice and training, we might then be able to do this more accurately and say what interval (how many semitones) separates them… but in order to do that, we first need to learn how we quantify such things!

Tone Deaf?

Some people will claim to be ‘tone deaf’. Theoretically, these are folk who have failed to develop the skills to identify different pitches on their own. However, this is largely a myth…. If someone was genuinely ‘tone-deaf’, they would not be able to hear the difference between the treble and tenor, all bells would sound the same and everything would (quite literally) be ‘monotonous’! In most cases, ‘tone deafness’ is about learning to control the singing voice and nothing to do with ears not working… It is more probably about getting over the stigma of being told to ‘be quiet’ by an ignorant teacher because they sang out of tune at school! With a little help, most can quickly develop their relative pitch and maybe even then develop and control their voice too… but that is another story and nothing to do with ringing!

Perfect Pitch?

However, there is another, much smaller and very select group (the remaining 0.1%) that can do much more…. These people have ‘perfect pitch’ and it enables them to identify and accurately remember an absolute pitch. It is something that most are just born with and it is not something which can be taught. People with perfect pitch can therefore tell you which key your ring of bells is in and instantly tell you that your bell is a slightly sharp G, or that although x tower’s bells are in F#, they are actually a bit flatter than y tower’s bells – which are also supposedly in F#…. and all without any other help or tools… they just know! Even amongst professional musicians, it is a relatively rare skill.

My daughter has perfect pitch and she was described by her music teacher as a ‘walking tuning fork’… She could accurately tune the school orchestra to 440Hz, without the need of a reference… Quite remarkable!

In practice, although a wonderful ability, perfect pitch can create all sorts of complications of ringers, because ringing Cambridge on one ring of bells will sound completely different to ringing on another and they may need to potentially transpose all the notes in their head!

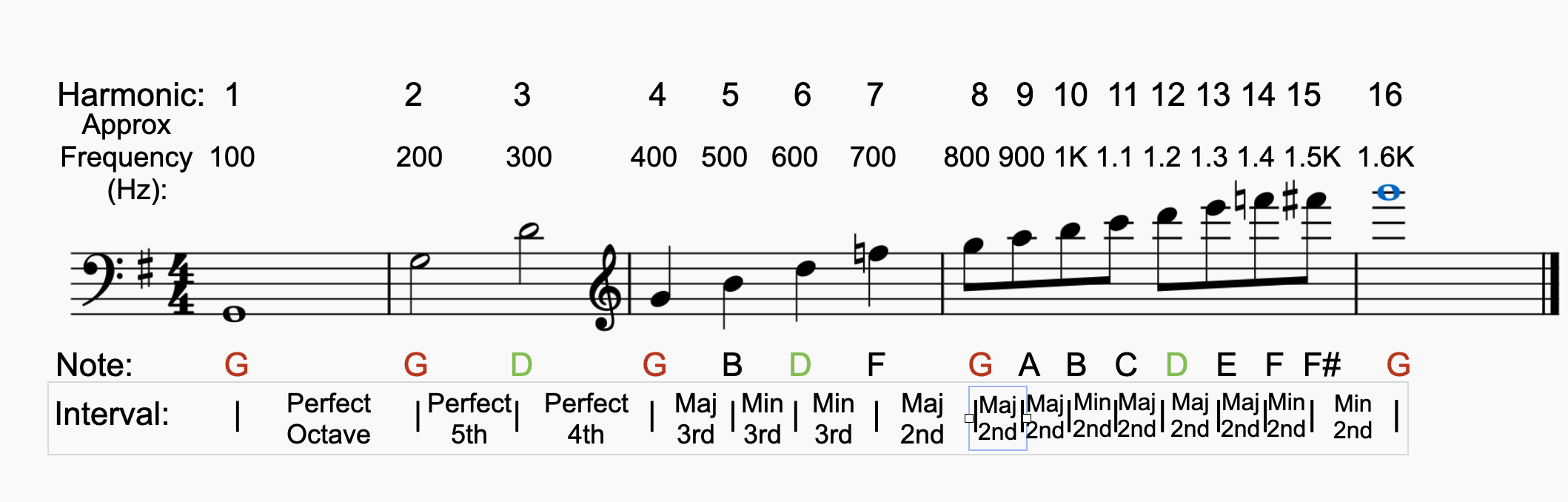

The Harmonic Series.

If you have read our article about the sound of bells, you will know that sounds are constructed from harmonics. These are multiples of the frequency we hear as the bell’s note.

The harmonic series is also the starting point for most of the common intervals we hear in our changes. As we multiply the fundamental frequency, it churns out all the notes we need. Generating a scale this way is referred to as ‘Just temperament”.

Below is a harmonic sequence based on the note G. We have shown it in musical notation as well as approximate frequency, note and the intervals between.

Equal Temperament

Although the harmonic series and ‘Just’ temperament actually makes an excellent basis for tuning our bells, it provides a unique set of number which are only useful in one key. We have since moved on and western music now has a tweaked version of it which allows us to work in any key. This is called ‘equal temperament’ and was developed 300 years ago at the time of JS Bach… Bach famously wrote his ’48 Preludes and Fugues’ using every possible key, to prove that equal temperament worked. The maths is quite complex, but in simple terms, it adjusts everything up or down a tiny, tiny fraction to make everything average out.

Because bells are almost exclusively diatonic (in one key), they could happily use ‘Just’ temperament, but our ears are now used to hearing the equal temperament tuning and expect it, so the specifics of bell tuning will normally be closest to that… purely for aesthetic reasons.

For really accurate tuning, each semi-tone (the smallest whole interval) is broken up into 100 cents… so if you see information about a bell being 34 cents sharp, it means the note is about 1/3 of a semitone higher than the ideal… That is actually quite a lot, so it will probably sound a bit out of tune assuming the others bells are not equally sharp. Remember everything is relative!

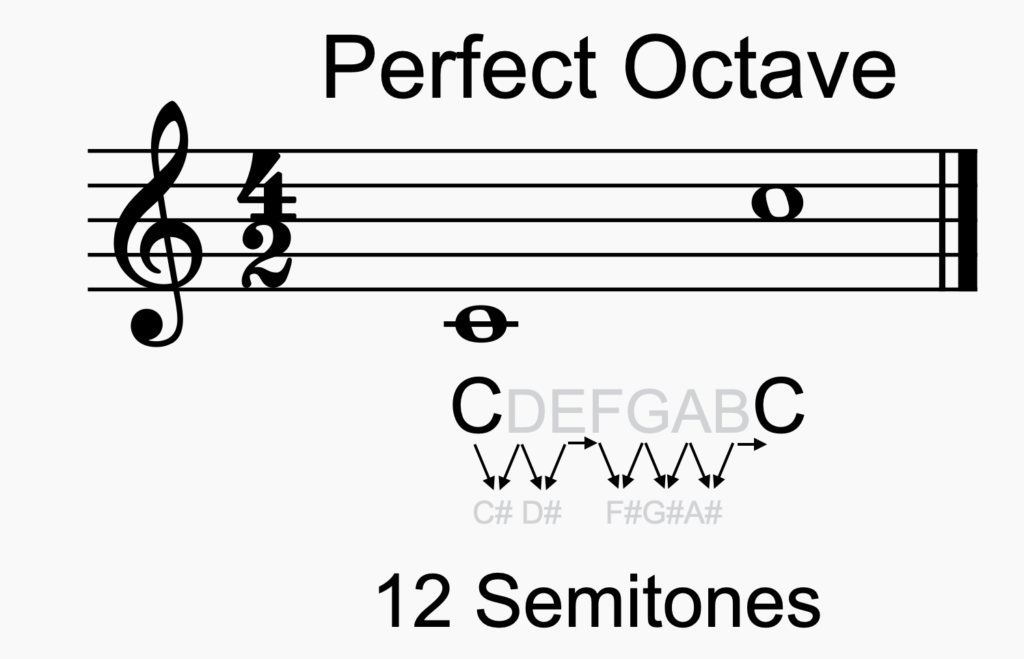

Perfect Intervals

Perfect Intervals are those which blend best…. their frequencies being very closely related. To our western musical ears, they produce sounds which are neither pleasing nor displeasing…. and perhaps a little bland! All the examples below are just that… So the notes can vary, and the important factor is the gap – the number of semitones! In a diagrams, the semi-tones are represented by the tiny arrows.

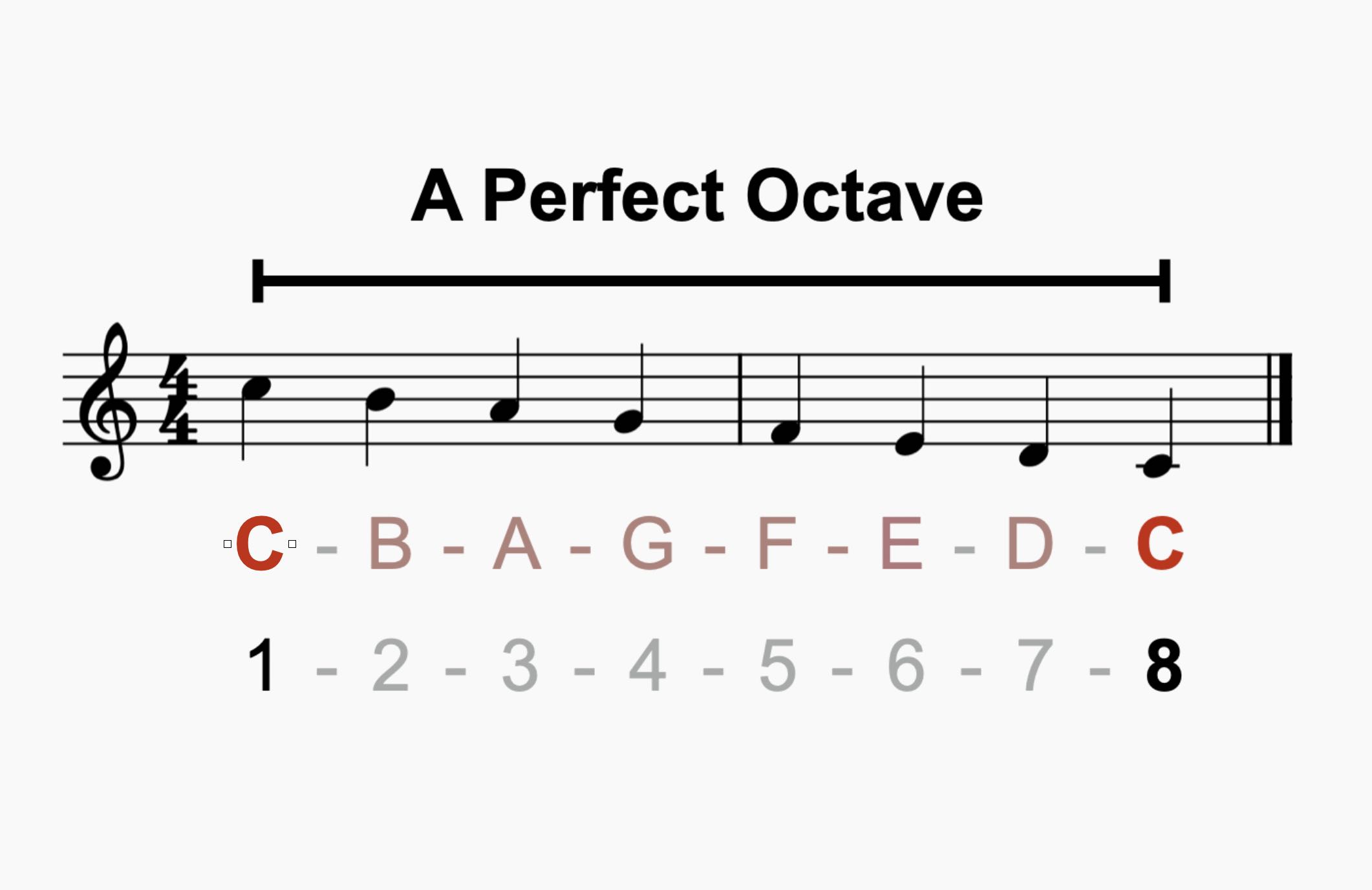

Perfect 8ve.

A Perfect Octave interval is 8 whole notes apart as the ‘Oct’ name suggests. The notes share the same letter name. The two frequencies will be related as a 2:1 ratio. e.g 200Hz and 400Hz.

When we sing or play in unison, everyone will be playing or singing the same notes… however, maybe one or two octaves higher or lower depending on the range and size of the instrument.

Men’s voices are generally 1 octave lower than women’s voices.

The notes sound the same because every wave of the lower note is perfectly aligned with a wave of the higher note.

Ringing

You will not hear an octave in 6-bell ringing – there are not enough bells! In 8-bell ringing there is only one possible octave when treble and tenor are adjacent… (e.g. in rounds!).

In Royal, bells 1, 2, and 3 will share an octave with 8, 9, and 10 respectively and for Maximus, it will be the front 5 and back 5 which are a prefect octave apart.

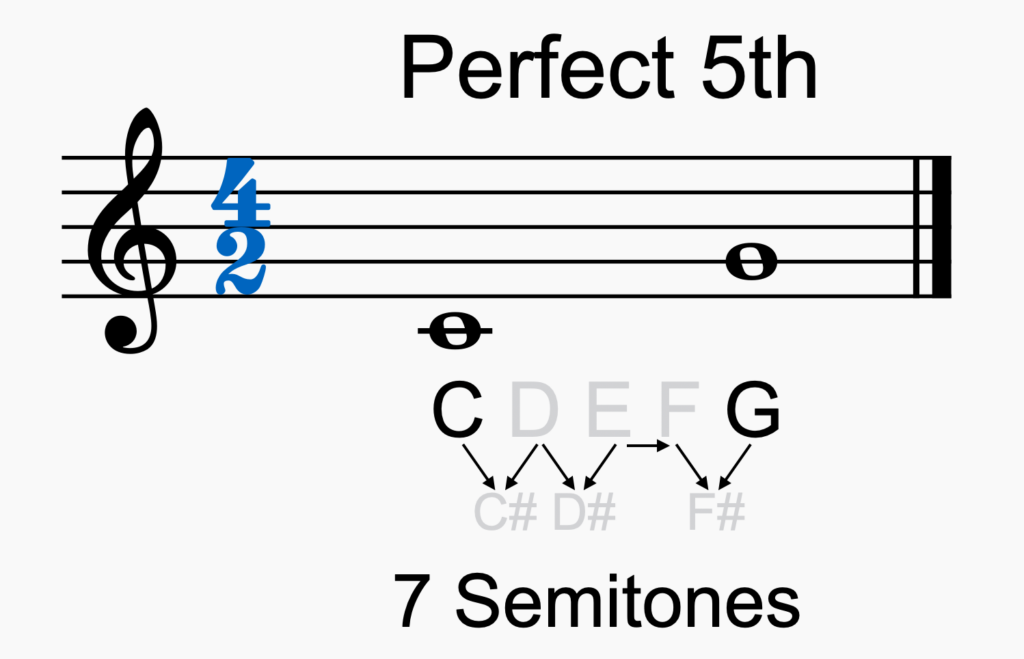

Perfect 5th.

A perfect fifth interval is a gap of 5 notes. The notes will blend very well, but not quite a well as the octave. The relationship is a 2:3 ratio. e.g a note at 200Hz will have a fifth above at 300Hz. It means the lower frequency is aligned with the upper note 50% of the time.

Singing in 5ths was very popular in medieval music and was called ‘organum’.

If you need to remember what a perfect 5th sounds like, think about the opening notes of Baa, Baa Black Sheep.

Ringing

We will hear a perfect 5th whenever the treble and 5, or 2 and 6 are adjacent in 6-bell changes.

In 8-bell ringing, perfect 5ths will be heard between any front/back pair of bells, e.g.Tittums, where pairs of bells in perfect 5ths are heard…. 15 26 37 48. In 10-bell ringing, there will be 6 different pairs possible, starting 1-5 and ending 6-10. In Tittums, it is the upward changes that will be perfect 5ths. e.g. 1-62–73-84–95-0.

Most 4 bell gaps will provide a perfect 5th…The exception will be 2-6 in Maximus, where this interval is a diminished 5th (see below).

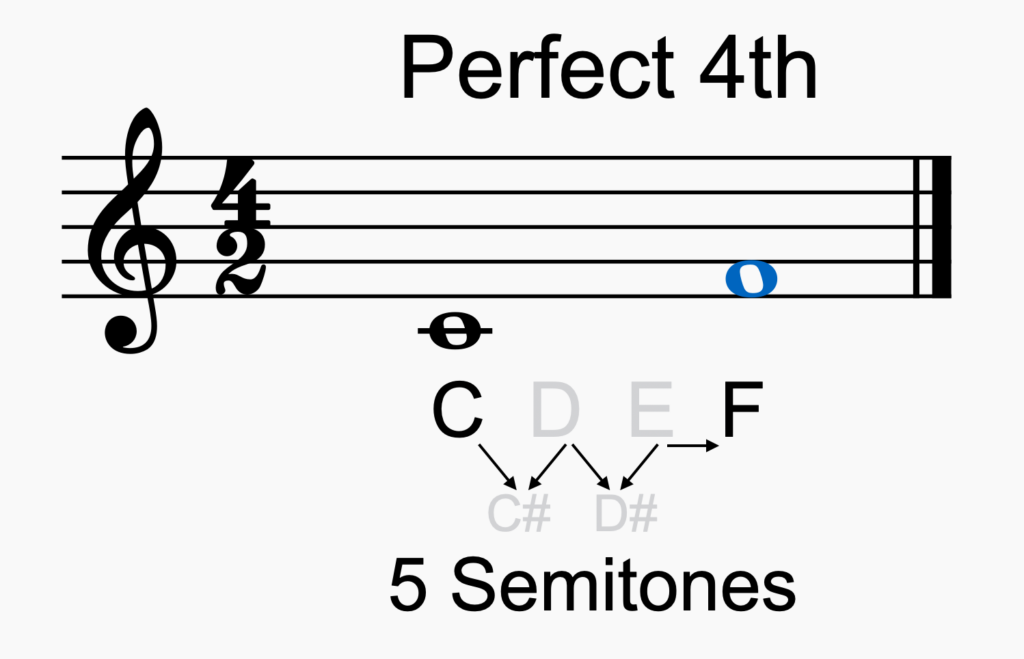

Perfect 4th.

The perfect 4th interval is the least perfect of the set… The notes will still blend, but will not sound quite as pleasing as either the octave or the 5th. The mathematical relationship is 3:4, so a 300Hz note and a 400HZ note will be a perfect 4th apart. The lower note will align every third wave, so 33% of the time.

If you need to remember what this sounds like… think of the opening notes in ‘The British Grenadiers’ or the carol ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’.

Ringing

As the interval shrinks, so the number of possibilities rise… As a good rule of thumb, nearly all 3 bell gaps, e.g. 1-4, 3-6, 4-7 or 5-8, will offer a perfect 4th. The exceptions are 2-5 in 8-bell ringing and 4-7 in 10-bell ringing. The exception for Maximus is 6-9.

Once again Tittums is the best example of using lots of 4ths… On 6-bells it is made by three perfect fourth pairs…. 14 25 36 and in Tittums major it is the upwards jumps which are perfect 4ths… 1-52-63-74-8.

Consonant Intervals

Together with the perfect intervals, the consonant intervals are used to create chords which sound pleasing to the ear. The waves they produce are still fairly closely related and thus align quite frequently. They provide the lions share of harmony in western music. Combinations of these intervals in changes provide a very pleasing sound… e.g. Queens, Whittingtons, etc.

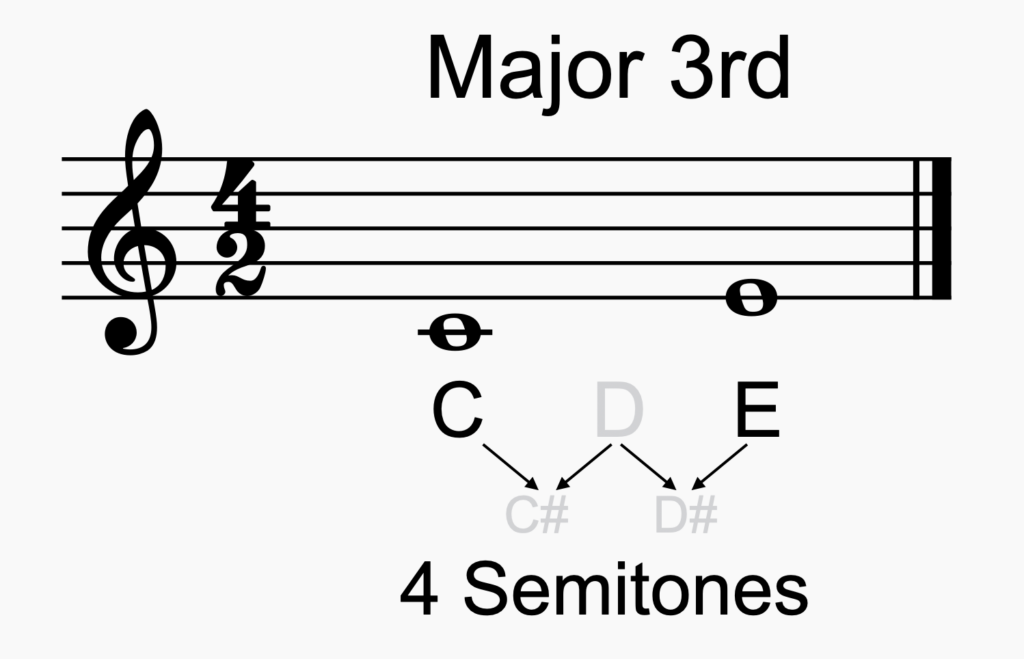

Major 3rd.

The major third interval is the next interval in the harmonic sequence and has a 5:4 mathematical ratio between the notes, e.g. a 500Hz note will be a major third higher than a note at 400Hz. This means the lower pitched note will align with the upper note, 25% of the time.

A major third is the biggest identifying factor of a major scale and provides a bright sound that is the third note of the scale. It is also used as the middle note in the tonic chord or arpeggio.

If you need to remember the sound… think of the opening notes of the carol ‘While Shepherds watched’.

Ringing

In 6-bell ring the interval between 1 & 3 and 4 & 6 are major thirds.

For eight bell ringing, the major thirds are between 2 & 4, 3 & 5 and 6 & 8.

With 10-bell ringing it is 1 & 3, 4 & 6, 5 & 7 and 8 & 10.

Perhaps the most notable use of thirds is in Queens and Whittingtons… which both alternate between major and minor thirds.

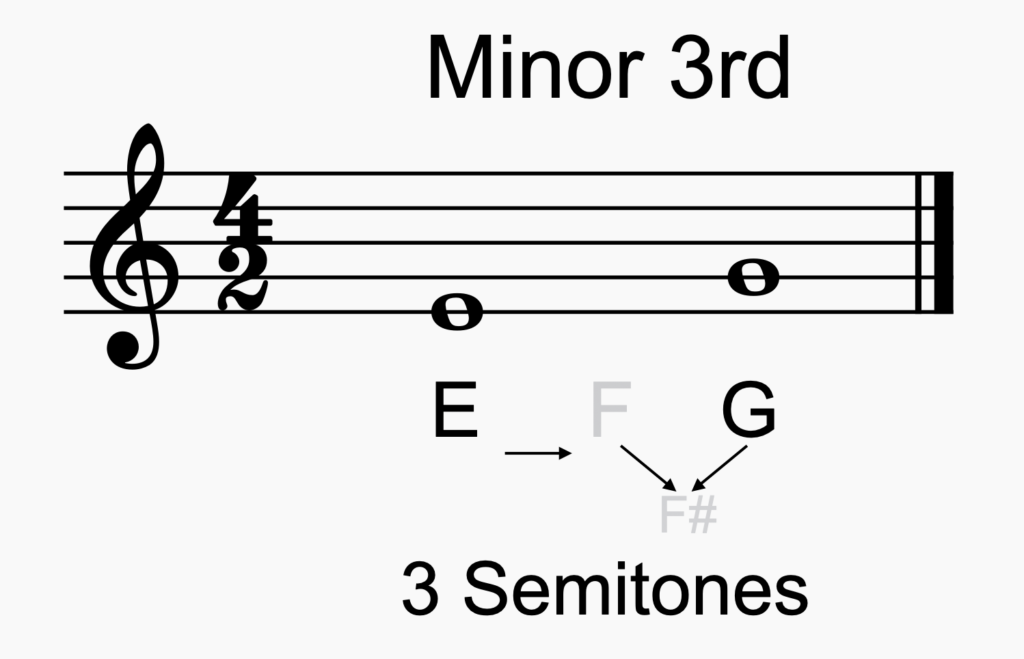

Minor 3rd

A minor third interval is found in the gap between the 5th and 6th harmonics and between the 3rd and 5th notes of a major scale. It has a mathematical ratio of 6:5, e.g. a 600Hz note is a minor third higher than a 500Hz note which keeps the waves aligned every 5th wave, or 20% of the time.

In a minor scale the important element is the minor third between the 1st and 3rd notes of the scale and the major third will be between the 3rd and 5th… so the exact opposite of a major scale. It is not so bright sounding as a major scale…

A good example of a minor third is the opening of Greensleeves.

Ringing

Minor thirds are found in 6-bell ringing between 2 & 4 and 3 & 5.

With 8-bell ringing, it is between 1 & 3, 4 & 6 and 5 & 7.

In 10-bell ringing, it is 2 & 4, 3 & 5, 6 & 8 and 7 & 9.

As per the major third, the most notable use is in Whittingtons and Queens , where it alternates with major thirds.

Minor 6th.

The Minor Sixth interval is the inverse to a major third. If you go from the third note of a major scale to the top note, that is a minor sixth. The ratio is between two higher harmonics… so between the 5th and 8th… which is a 5:1 ratio and means that alignment is still 20% of the time.

Ringing

Because it is a large interval, it is more common in higher number ringing.

It is not possible to have a minor 6th in 6-bell ringing…. Not enough bells.

In eight bell ringing, there is only one minor 6th. It is between 1 & 6.

With 10-bell ringing they are between 1 & 6, 3 & 8.

Major 6th.

A major 6th interval is the inverse of a minor 3rd. It is found between the 1st and 6th as wells as the 2nd and 7th notes of the scale. The ratio is between two higher harmonics… the 3rd and 5th harmonics. This provides a 33% alignment.

Ringing

Because it is a large interval, it is more common in higher number ringing.

There is only one 6-bell major 6th… between 1 and 6.

In 8-bell ringing, major 6ths are between 2 & 7 and 3 & 8.

With 10-bell ringing, the major 6ths are found between 2 & 7, 4 & 9 and 5 & 10.

Dissonant Intervals are those which have frequencies with less and less mathematical relationship. These will often be notes that are adjacent in musical scales… In harmony, these intervals will provide the spice and crunch when combined in moderation with the constant and perfect intervals. Used on there own, they can provide a sound which can be harsh and unpleasant.

Dissonant Intervals

In western harmony, these intervals will provide a distinct crunch when combined! The mathematical relationship between waves is getting more obscure! In ringing, we do not really worry about harmony and these intervals will provide the basis of many changes, as we more up or down a scale. Some of the larger intervals however, might sound unfinished or less appealing when at the beginning or end of a change.

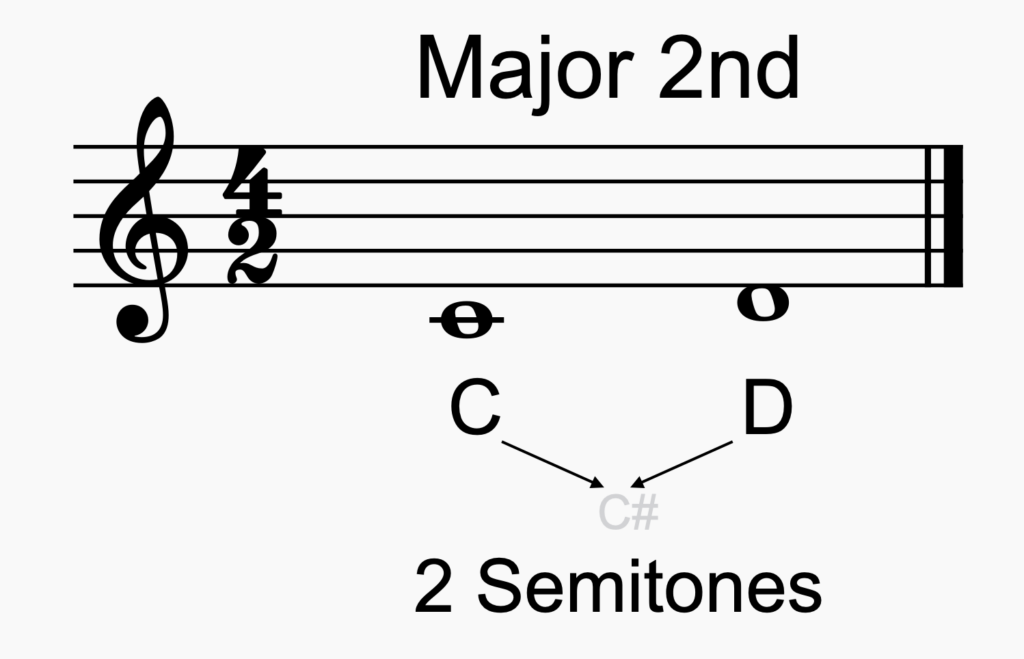

Major 2nd.

The major second intervals is the gap between 5 pairs of notes in a major scale.

In theory, the seconds in the Just temperament scale are all different sizes, which makes things very complex. Because we use the equal temperament tuning, it makes all major 2nds the same size… A major second will be two semi-tones, which will mean frequencies will align round about 1 in every 6 waves.

If you want something to help you remember the sound… think of the second and third notes of the National Anthem…. ‘God Save Our.…’

Ringing

There are 4 pairs in 6-bell ringing, 5 pairs in 8-bell ringing and 7 pairs in 10-bell ringing, so these intervals are probably the most common that we will hear when ringing changes.

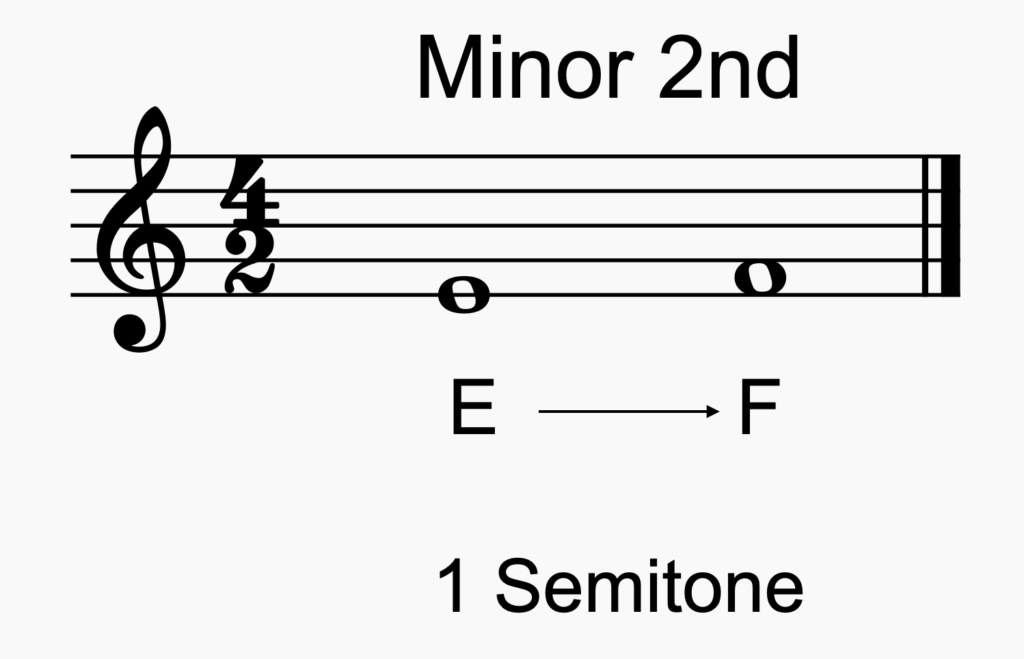

Minor 2nd.

A minor 2nd interval is the smallest gap found in a scale and is found between the 3rd & 4th and 7th & 8th notes of a major scale.

Because we use the equal temperament scale, all minor 2nds are the same size and are 1/12th of an octave…. i.e. one semi-tone. So waves align only once roughly every twelve cycles if played together.

If you want something to help you remember the sound… think of the last two notes of the National Anthem… ‘God… Save Our King.’

Ringing

Because most rings are major scales, we do not find many minor seconds in changes.

6-Bell ringing has only one between bells 3 and 4.

8 & 10-bell ringing both have 2…. Between 1 & 2 and 5 & 6 for 8 – bell and 3 & 4 and 7 & 8 in 10-bell.

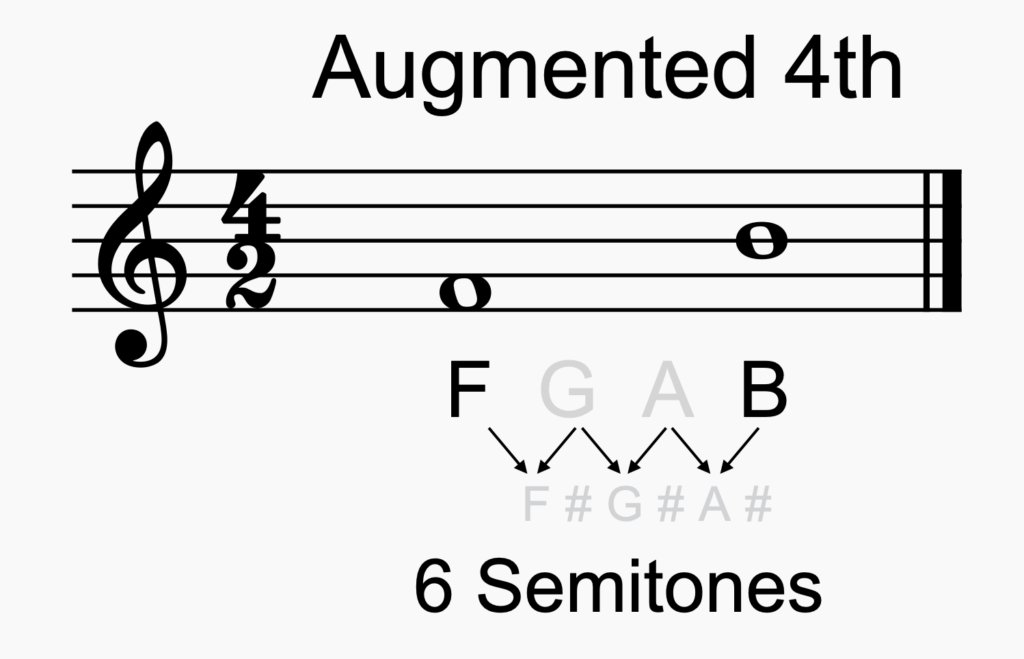

Augmented 4th.

The Augmented 4th interval is 6 semitones, which appears to be half a 12 semi-tone octave. However, it does not sound like half an octave and only aligns relatively infrequently. The perfect 5th is the genuine scientific half!

The sound is something we will not find as natural or pleasant to listen to… it is quite dissonant and most will find it difficult to pitch or sing accurately.

It is sometimes called a tri-tone, because it consists of three whole tones.

Ringing

The augmented 4th appears once in both 8-bell and 10 bell ringing. It is between bells 2 & 5 for 8-bells and 4 and 7 in 10-bell ringing (the same place). It does not appear in 6-bell at all.

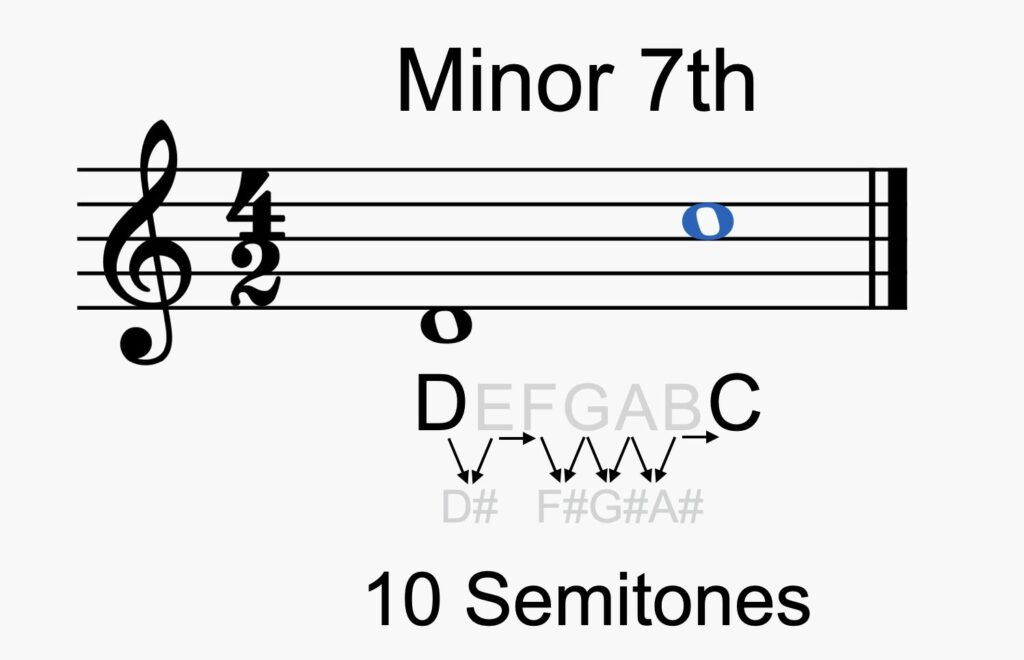

Minor 7th..

The minor seventh interval is formed by the 4th and 7th harmonics of the series. It is very commonly used in western music and appears between notes 2 and 8 in a major scale. It is also the inverse of the major 2nd. It has 10 semitones.

Ringing

With spacing of 7 notes, it cannot occur in 6-bell ringing, but does occur once in 8-bell, twice in 10-bell ringing and four times in twelve. The pairs are 1-7 for 8 bells and 3-9 and 2-8 for 10-bell. In twelve bell, it is 5-11, 6-10, 2-8 and 1-7.

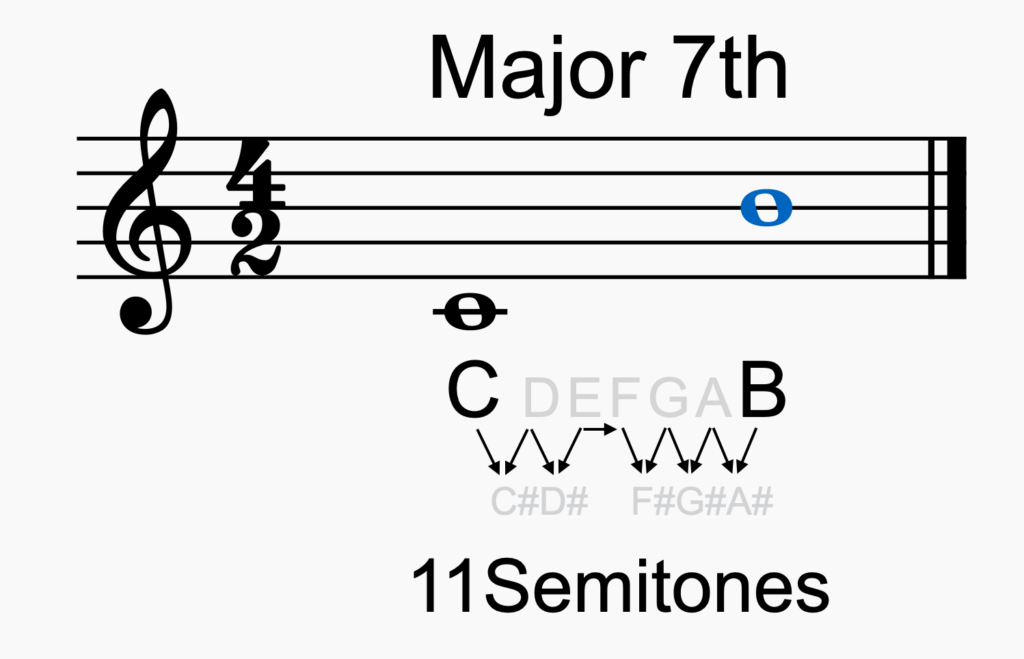

Major 7th.

A major 7th interval is 11 semitones… so just one short of an octave. As a result, the sound waves only align about 9% of the time and we hear the interval as very dissonant. It appears in the major scale between notes 1 and 7.

Ringing

With 7 notes, it cannot appear in 6-bell ringing.

However, in 8-bell it appears between bells 2 and 8, and 4-10 for 10-bells.

In 12-bell, it appears between 3-9 and 6-12.

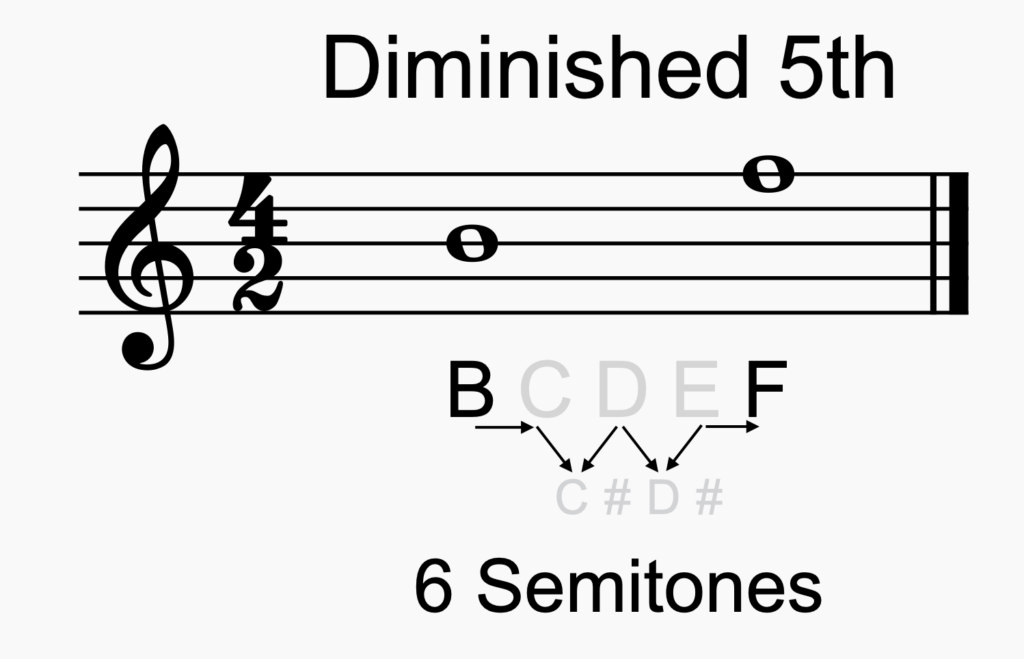

Diminished 5th.

A Diminished 5th interval is 6 semitones…. the same as an augmented 4th in terms of sound…. however, it is formed of notes which have 5 notes names of spacing. In the simplest scale, if you jump from the 7th note of a scale (bell 6 in a twelve bell ring) up to the fourth note of the octave above (bell 2 of twleve) it is 5 notes of gap, but only 6 semitones.

The sound of a diminished 5th is not something that sounds natural to us and most people would find it difficult to sing accurately. It is quite dissonant.

It is sometimes called a tri-tone, because it consists of three whole tones.

Ringing

The Diminished 5th is only found in a twelve bell ring (or more!)… between bells 2 and 6.